Hungary fighter who whetted our appetite for Rigo and co

HUBBARD’S CUPBOARD – 13.2.16

By Alan Hubbard

For years now exiles and émigrés have long been an major component in the rich fabric of boxing, dating back well before the lifting of the Iron Curtain in 1991. This opened the floodgates for such as the Klitschkos and now those big-hitting Beasts from the East, Gennady Golovkin and Sergey Kovalev to exert so much influence on the professional game.

But arguably the most productive examples of totalitarian regimes where punching for profit was strictly taboo, are the Cubans.

A whole stream of fine fighters have made the 90-mile journey across the Straits of Florida from their Communist homeland to Miami to launch professional careers careers culminating in world domination.

The list of Cuban émigrés who became fed up with Fidel Castro’s no pay policy in an island nation steeped in boxing history seems endless.

Olympic legends Teofilo Stevenson, Mario Kindelan, and Felix Savon declared they’d rather be red than rich, and stayed loyal to their fatherland despite tempting offers from professional promoters in the US and Europe.

”What is eight million dollars compared to the eight million Cubans who love me?” declared the late three-times times Olympic heavyweight champion Stevenson, a ko king whom I dubbed Castro’s right hand man.

But the trickle of boxers escaping Cuba decades ago has now morphed into a veritable tsunami.

To name but a few of the great Cuban defectors: Benny Paret, Luis Rodriguez, Sugar Ramos, Jose Napoles, Jose Legra, Joel Casamayor, Erislandy Lara and Guillermo Rigondeaux.

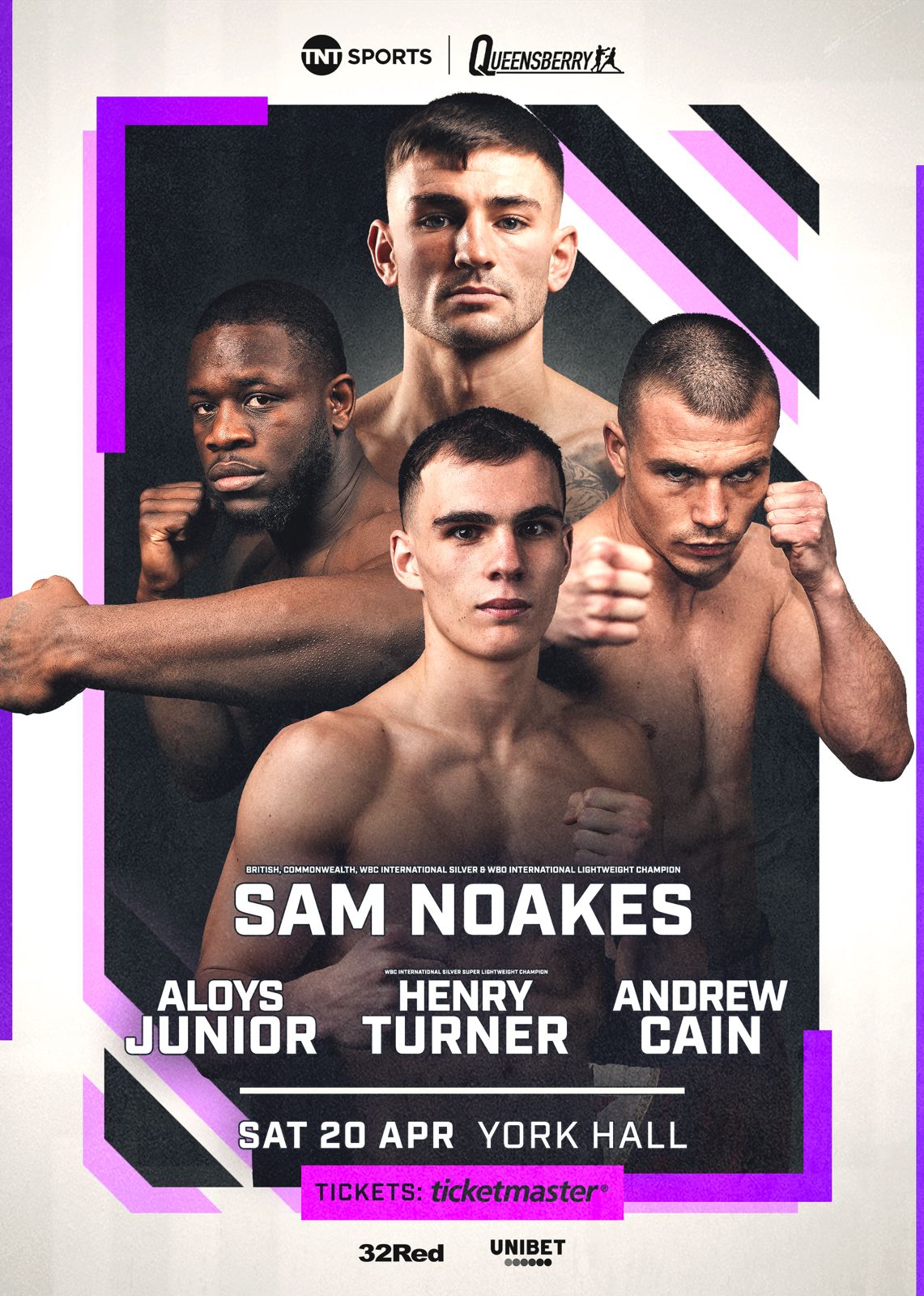

Rigo, one of the all-time great super-bantamweights, will exercise his silky skills in Liverpool on March 12, against gutsy Scouser Jazza Dickens, a real coup for Queensberry Promotions.

Now even China, where red is also still the political hue, is muscling in on the pro boxing act.

Top Rank say that Zhou Shiming’s TKO win over Natan Santana Coutinho in Shanghai last month drew a total of 36.5 viewers there, with 6.5m tuning in on television and the remaining 30m watching via live stream. There were also 12,000 in attendance at the Oriental Sports Centre.

But back to the Iron Curtain. As Steve Bunce wrote in The Independent last week, Mate Parlov, from Yugoslavia, was the first professional world champion from a Communist land.

He won the Olympic gold in Munich at light-heavyweight and also won two European titles and walked away from the amateur sport with 310 wins and just 13 defeats.

Parlov, who controversially defeated Britain’s John Conteh on a split decision in Belgrade in 1978, may have been the first world champion from behind the Iron Curtain but the real pioneer for those who eventually were to shake off the shackles of communism and earn a crust by capitalising on their fistic talents was arguably the greatest amateur of them all, Laszlo Papp.

The Hungarian may not have been the most exciting fighter ever to pull on a pair of gloves but he had the perfect pugilistic pedigree.

The former railway clerk was the first boxer to win gold medals at three successive Olympics.

The first fighter from the Soviet bloc to turn professional, he was already 31 when he joined the paid ranks, but went on to capture the European middleweight crown, make six successful defences and retire undefeated.

Remarkably, he lost just 12 bouts in a 300-fight amateur career. Then he went to see the minister in charge of sports, “who gave me the nod” to fight for pay.

Although professional boxing continued to be outlawed in Hungary – and Papp was never permitted to fight there – he set up camp in Vienna, and proceeded to work his way up the rankings by beating several top-ranked contenders, including the formidable Peter Muller and Ralph ‘Tiger’ Jones.

A hard-hitting southpaw with excellent movement and a searing left hook, Papp woned the European 160lb crown by knocking out Denmark’s Chris Christiansen on in May 1962, and was rising 39 when the belated chance to challenge Giardello arose.

But he was recalled to Budapest from his training camp in Vienna on the pretext of consultations – “and then they revoked my passport”. Papp had actually been a professional for eight years when the Hungarians effectively ended his career by refusing to allow him to leave the country, saying that fighting for pay was incompatible with the country’s socialist principles.

For once Papp was reluctantly forced to throw in the towel. “I believe I had a good chance of winning the title as I had defeated others who defeated Giardello,” he said. “This is my one big regret in life.” He retired undefeated having won 27 fights, 15 by knockout, and drawn two.

The fact that Papp’s professional career ended on a sour note could not overshadow what he had achieved as an amateur. He secured lasting fame by winning Olympic gold at middleweight in London in 1948 (outpointing Britain’s John Wright), and at light-middleweight at Helsinki in 1952 (beating South Africa’s Theunis van Schalkwyk) and Melbourne in 1956.

This last victory, against the future world champion, Puerto Rican Jose Torres, sparked scenes of great emotion, as it came in the grim aftermath of the crushing of the Hungarian uprising.

In fact, Papp always claimed he would have won a fourth gold medal at the Rome games of 1960, “but I wanted to make some money.”

Like many fierce punchers, he suffered brittle bones, and hand injuries occasionally kept him out of the ring. He was already 36 when he became European middleweight champion but, over the next three years, Coventry’s Mick Leahy was the only challenger to survive to the bell. He defended his European crown six times, his final triumph coming on points against Leahy in Vienna in October 1964.

In retirement, Papp coached the Hungarian national team from 1971 to 1992. In 1989, the WBC named him an honorary world champion, “perhaps knowing I would have had a pretty fair chance of taking the title from Giardello”. Two years later, the Council designated him the world’s best amateur and professional fighter of all time.

Following Hungary’s return to democracy in the early 1990s, Papp ran a boxing school, and was inducted into boxing’s International Hall of Fame in 2002.

He died a year later, in October 2003, aged 77, but his enduring epitaph will be that he paved the way for boxers from repressive regimes to literally become freedom fighters.

Tomorrow catch up with Alan Hubbard’s Punchlines exclusively at frankwarren.com